By Regan Crider, May 2023

Greetings! My name is Regan Crider, and I’m a fourth-year anthropology student at the University of Oklahoma. For over a year, I’ve been involved with the archaeology department at the Sam Noble Museum, first as a volunteer and then twice as an intern. During my first internship in the fall of 2022, I worked on a NAGPRA collection, which involved learning about Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. If you’re interested in this topic, you can check out the Bureau of Land Management’s article on NAGPRA, which is accessible through this link: https://www.blm.gov/NAGPRA.

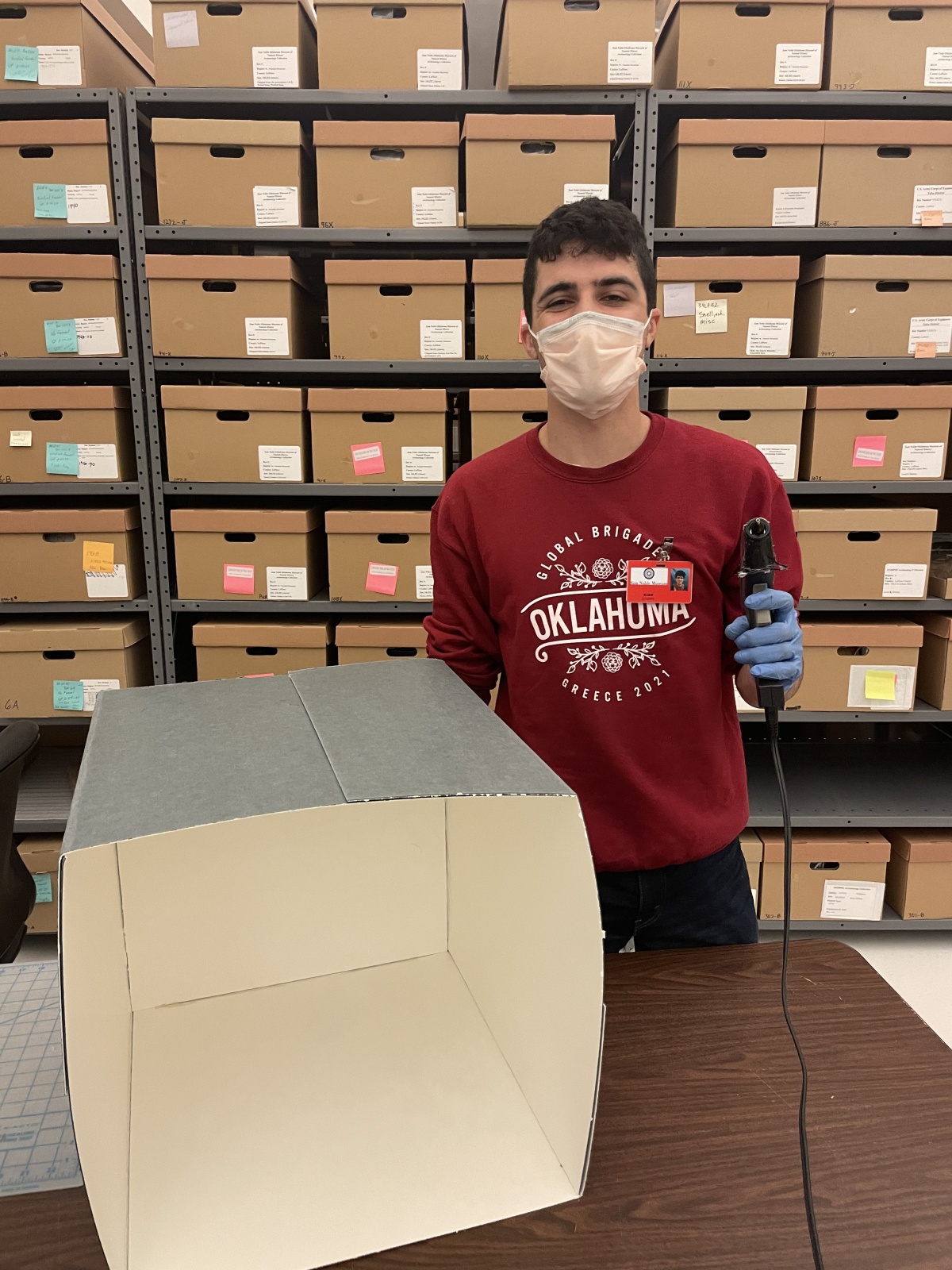

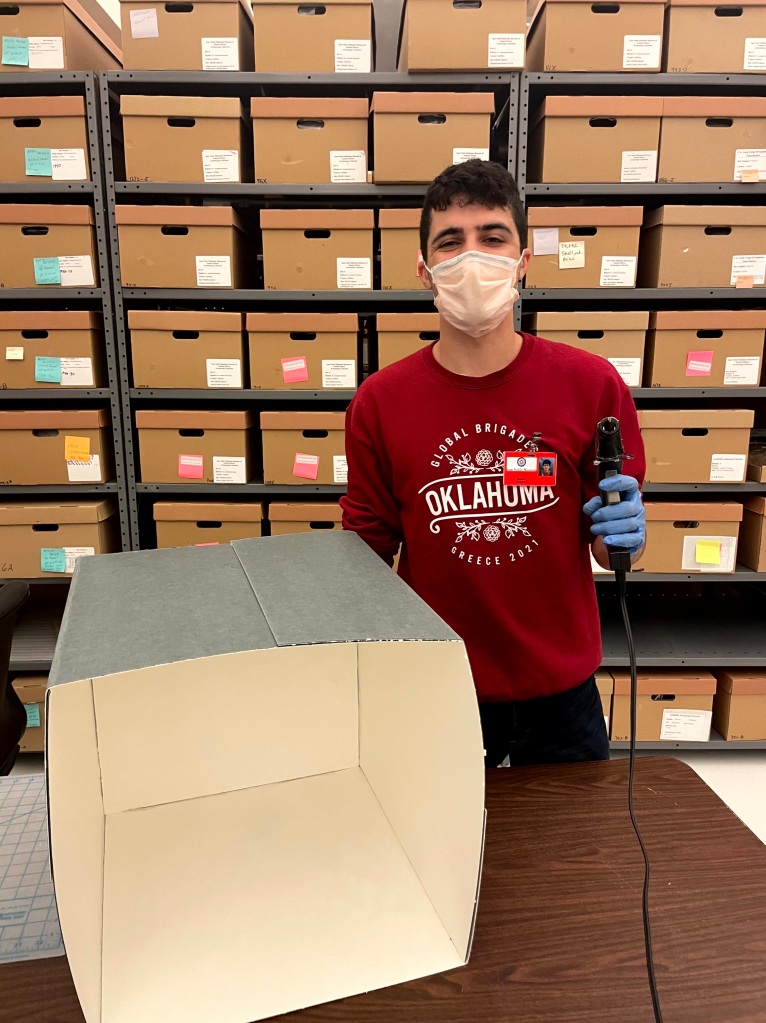

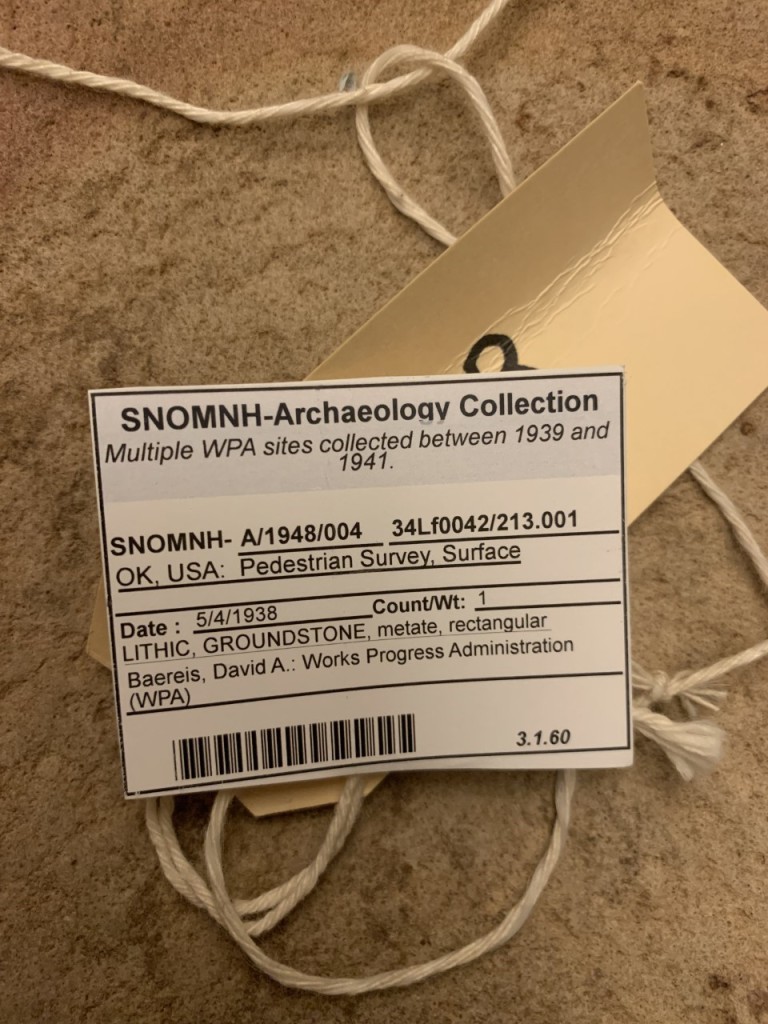

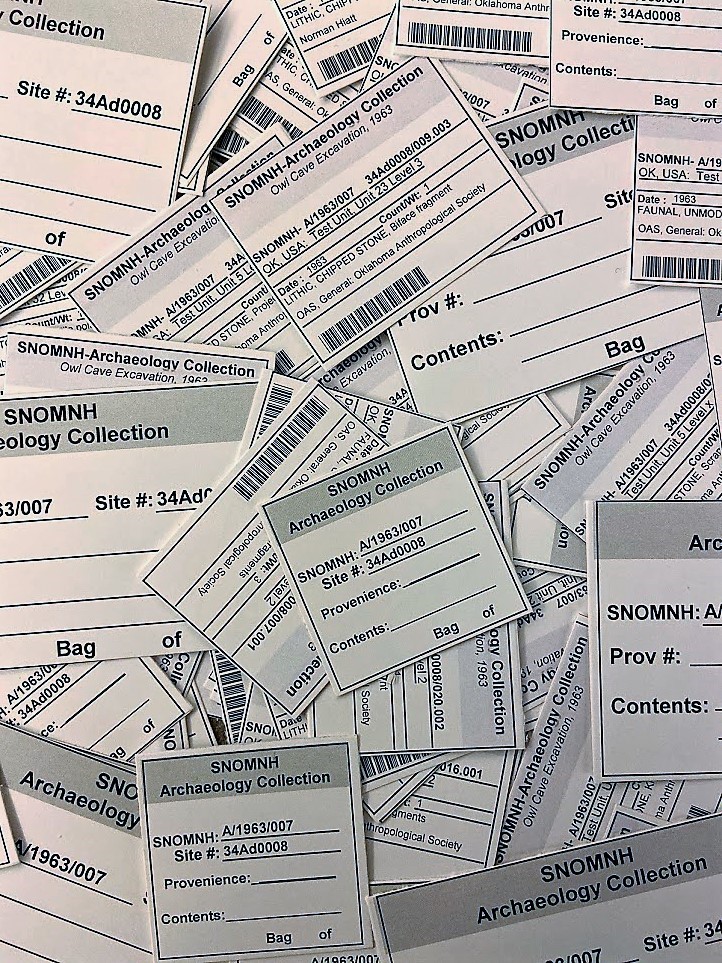

For my first internship, I assessed (inventoried) a large collection (154 cubic feet). NAGPRA, or the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, was not a new or unfamiliar concept to me. The goal of assessment is to assure that every artifact listed in our records is physically accounted for and no funerary objects are missed.

As an anthropology student with an archaeological focus, I had learned about NAGPRA in a few of my classes, but I didn’t understand how it actually worked. This first internship allowed me to better understand how NAGPRA was implemented in a museum and gain hands-on experience working with a collection that would someday be repatriated. My experience interning at the museum has been a wonderful educational opportunity but also an incredibly rewarding one, as I have been able to do my part in helping return artifacts to their rightful owners.

When Susie Fishman-Armstrong (Archaeology Collection Manager, NAGPRA Coordinator) asked me to return for a second internship, I was thrilled to accept. While I had enjoyed my first internship, I knew that there was much more to learn about collections work. Although I had become familiar with assessment and NAGPRA procedures, I wasn’t sure what to expect when Susie told me that I would be working on managing our department’s loans and acquisitions.

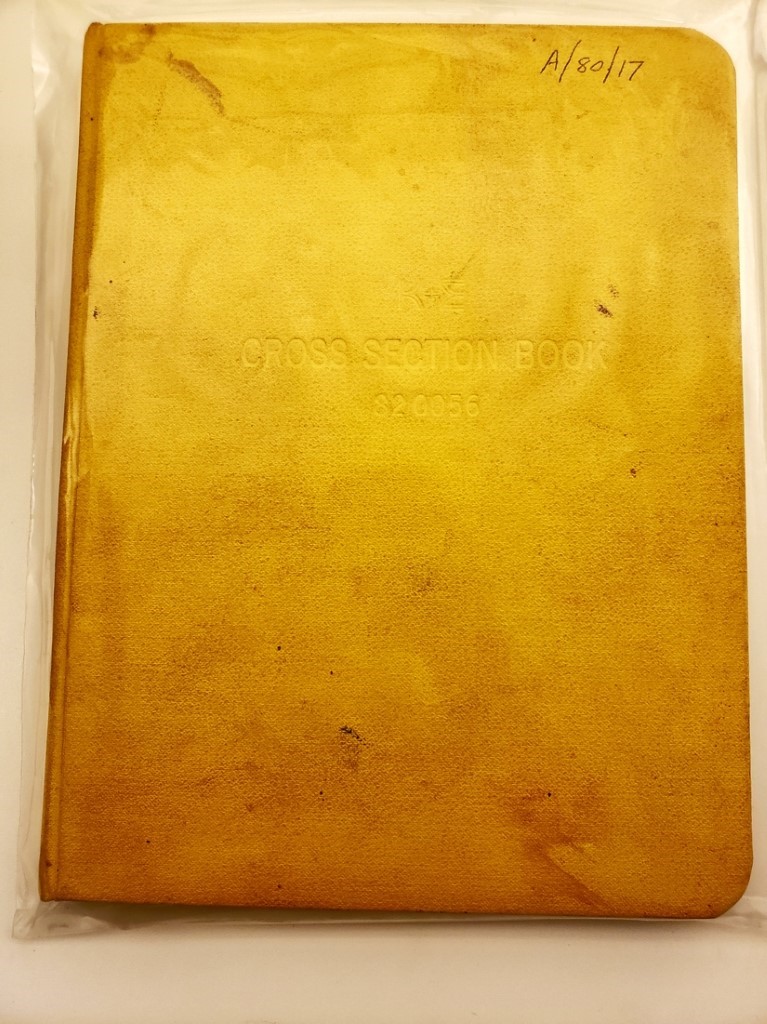

While I was excited to learn the administrative aspects of Susie’s work, I knew I would miss the hands-on work with the artifacts I did during the first internship. I had grown to enjoy the challenge of assessing collections and solving puzzles like finding misplaced artifacts or correcting discrepancies. However, I quickly discovered that loan management was a complex puzzle in its own right.

The Sam Noble Museum’s loan program is an important part of fulfilling its mission: to inspire minds to understand the world through collection-based research, interpretation, and education. Loans enable other institutions or researchers to access the museum’s treasures, supplementing new ideas or showcasing old ones.

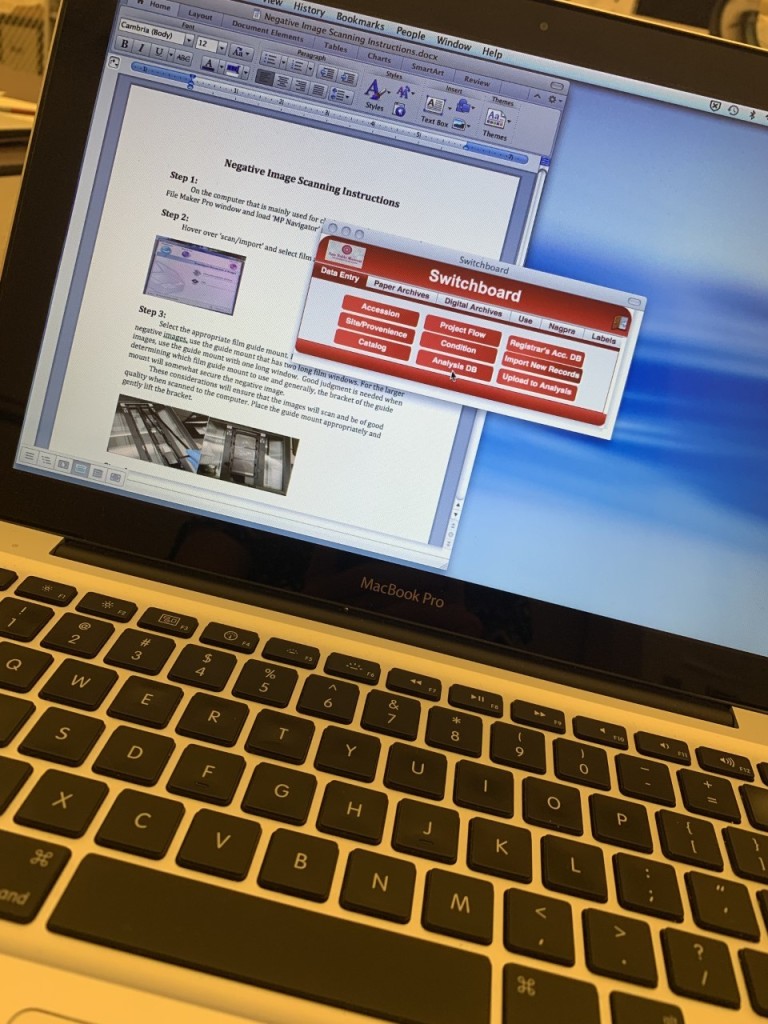

However, the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on loan management and other aspects of the museum’s operations. When I began this semester, Susie showed me a stack of files containing all the loans I would be working on. Due to the pandemic’s disruptions, many of these loans had expired or needed to be updated. My task was to gather information for each loan, such as who requested it, when was the last correspondence, and whether they still had it. I had to dig through our database, as well as make several emails and calls to track down the information.

The loan management process was not always straightforward, however. Sometimes, loans had been declared closed prematurely without proper paperwork or final reports. In one instance, I discovered that a loan that had been closed a year ago was still at the Archaeological Survey, so I had to coordinate its return to the museum and complete an assessment to officially close the loan.

Overall, working on loans and acquisitions has given me a more well-rounded understanding of the archaeology department’s work and how it contributes to the museum’s mission. I’ve also gained many useful skills that will be valuable for my future career in museum work. I’m looking forward to returning to work with the Sam Noble Museum and learning more about my colleagues’ fascinating projects.